I was recently tasked with upgrading the servers of a small company. After defining the requirements and thinking about the architecture of the whole system, I decided to document the setup here as a guide, both as a reference for my future self (my memory works in a if-I-didn’t-write-it-down-it-didn’t-happen kind of way) and hopefully to help anyone trying to achieve similar results.

Don’t take everything written here as a promise of absolute best-practice. What I describe here fits well for my use case, but you might prefer other solutions, such as using Ansible to create the nodes, or a more modern log aggregation solution such as the ELK stack. This article will also be fairly long, so feel free to jump to the sections that are relevant to you and only take inspiration to build your own setup. I’ll try to link to the source documentations as much as possible to help you customize the configuration files to your need and help you make your own choices. If you think I made a mistake or you have suggestions to improve this setup, please leave a comment.

Table of contents

1. Requirements

The servers need to host all the services needed by the company, which include miscellaneous but pretty common things such as a Postfix/Dovecot mail server, a WordPress website, and internal webapps. The services to run may change on a regular basis, and I’d like to be able to migrate to another host provider as easily as possible if need be.

These services also need to be as isolated as possible in case one of them gets compromised (looking at you, WordPress). Some services are managed by external contractors which must be isolated from the other services.

The setup below will emphasize these two key requirements : flexibility, and isolation.

2. Architecture

2.1 Containerization

Docker is a good solution to clearly define the boundaries of each service, and isolate them from one another. It also makes it a lot easier to move services and refactor the architecture as needed. I’ll try to keep the base OS installation and configuration relatively minimal (or at least, standard), and run all services as Docker containers.

This goes toward both our key requirements : containers can be moved around more easily than bare-metal packages with configuration files and data all over the system, and they are relatively isolated from each other.

However, some services will need even a greater level of isolation :

- because they contain sensitive information (some internal webapps),

- because they run apps with a higher risk of being compromised (WordPress with some dubious plugins),

- or because they will be managed by an external contractor that requires restricted access.

2.2 Nodes

For this reason, I’ll separate the architecture into multiple VPS’s (virtual servers), that I will call nodes. All servers will share the same base domain name, that I will name mydomain.com 1 here, prefixed with the server’s node number. So the first server will be named n1.mydomain.com, and so on. Tying the name to the server (node) itself and not semantically to a service name means I will have more flexibility to add new nodes and move services around in the future.

N1 will be my central node, and will not contain any user-facing services. It will be used as a main server to centralize the information about and control over the other nodes and their services. It will have a slightly different configuration from the other servers. The other nodes (N2, N3, …) will share the same base configuration, and only differ by the Docker services that they run, again to make things as flexible and scalable as possible.

1 To make it easier to follow and adapt to your case, I will highlight in a different color the placeholders that need to be customized in the commands and config files.

3. Implementation

3.1 Hosts provider

All the servers will be hosted at Gandi, as GandiCloud VPS instances (not sponsored, just an FYI), and based on Debian 12 Bookworm.

3.2 Private network

They will be connected together via a private network, instantiated using Gandi’s web interface. This network is in the 192.168.1.0/24 range. This makes it easier to securely connect the nodes together, for instance by opening the ports of administrative processes only on the private network’s interface. However, if you would like to do the same thing but your provider doesn’t offer this feature, you can achieve similar results using appropriate an firewall configuration.

3.3 Centralized logging

I want to centralize the logs of all the nodes on N1. This will make it easier to troubleshoot issues, and safer in case one node is compromised or unresponsive, or if a contractor with root access on its dedicated node does something fishy and tries to cover their traces.

In order to prevent issues in case a large amount of logs suddenly fill up the storage, the logs will be stored in a separate volume mounted at /logs. They will be categorized by hostname following this file structure : /logs/<hostname>/<facility>/<process>.log1. For example : /logs/n1.mydomain.com/auth/sshd.log.

1 If you are not familiar with rsyslog, the “facility” can be seen as the category that the log belongs in : auth, kern, mail, daemon, …

Enough talk, let’s dive in. Most of the configuration will be common to all nodes, so we’ll use N1 as an example. I will make it clear in the few cases where there are differences between N1 and the other nodes.

4. Nodes configuration

4.1 DNS

After creating the server in Gandi’s web interface, we’ll configure mydomain.com for the hostname of the node in IPv4 and IPv6 :

n1 10800 IN A 46.X.X.X

n1 10800 IN AAAA 2001:X:X:X:X:X:X:XIn Gandi’s web interface, we also need to configure the reverse DNS on these IPs to match n1.mydomain.com.

Next, we can connect to the server via SSH :

$ ssh debian@n1.mydomain.comIf, like I did, you had the option to specify your SSH key during the creation of the server, you can connect directly without a password. Otherwise, copy it now by running this command from your local computer :

$ ssh-copy-id debian@n1.mydomain.comEverything we will do next will require root access, so let’s immediately change the current user :

debian@n1.mydomain.com$ sudo su4.2 System updates

Even though the server is brand new, the image that was used to install it might not be that fresh, so it’s always a good idea to make sure everything is up to date :

# apt update

# apt upgrade

# apt dist-upgrade

# apt autoremoveIf asked about conflicting files, I usually keep the version locally installed.

4.3 Hostname

We want to make sure that the hostname matches the FQDN of the node :

# echo "n1.mydomain.com" > /etc/hostname

# hostname -F /etc/hostnameCheck with :

# hostname

n1.mydomain.comWe also edit the hosts file to link this hostname to localhost :

# nano /etc/hosts

127.0.0.1 n1.mydomain.com localhost4.4 Date, time and timezone

It’s important that the server has the correct date and time in the local timezone to avoid issues with certificates and misunderstanding while reading logs. I’m in France, so I’ll use the Europe/Paris timezone :

# echo "Europe/Paris" > /etc/timezone

# timedatectl set-timezone Europe/ParisWe’ll also make sure that NTP is installed and running, in order to synchronize the time over the network :

# systemctl status systemd-timesyncdYou should see this service enabled and running.

Finally, check the current date and time with :

# date4.5 Private network interface

Skip this part if you don’t have a private network.

We will give the nodes private IPs in the 192.168.1.100 range, with the last digit the same as the node number to make it easier to memorize : 192.168.1.101 for N1, 192.168.1.102 for N2, and so on. The IPs for each node are statically configured in Gandi’s web interface and are served to the nodes via DHCP. If you don’t have this option, you will need to configure a static IP on each server.

Check the status of the network interfaces :

# netplan status --all

...

● 3: enX1 ethernet DOWN (unmanaged)

...The public network interface on enX0 is up and running, but the private interface on enX1 is down.

Side note : according to the logs, there is a misconfiguration that triggers a warning, that can be avoided by fixing the permissions of the default config file (this is probably specific to Gandi) :

# chmod 600 /etc/netplan/50-cloud-init.yamlWe only need to enable DHCP for this interface :

# netplan set --origin-hint 60-private-interface ethernets.enX1.dhcp4=true

# netplan applyApplying the new config may take a minute. After this, we can check the status of the interface again to make sure it is enabled and has the correct IP :

# netplan status --all

...

● 3: enX1 ethernet UP (networkd: enX1)

MAC Address: X:X:X:X:X:X

Addresses: 192.168.1.101/24 (dhcp)

...4.6 SSH

For greater security, we will only allow users to connect to SSH through key authentication, not using a password, by uncommenting the following lines in sshd‘s config :

# nano /etc/ssh/sshd_config

PubkeyAuthentication yes

PasswordAuthentication noThen we reload the daemon’s configuration :

# systemctl reload sshd4.7 Shell

This is a matter of personal preference, obviously you should adapt the instructions below to use your shell of predilection.

I like zsh with Oh My Zsh, let’s install them :

# apt install zsh git

# sh -c "$(wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/ohmyzsh/ohmyzsh/master/tools/install.sh -O -)"Now is a good time to customize the configuration. Here are a few settings that I usually set :

# nano ~/.zshrc

ZSH_THEME="agnoster"

export EDITOR='vim'

alias ll="ls -al"

alias dk="docker"

alias dc="docker compose"Find more themes and plugins in the official documentation.

4.8 Firewall

We’ll install ufw as a firewall, as it’s pretty easy to setup :

# apt install ufw

# ufw limit ssh

# ufw default deny incoming

# ufw default allow outgoingUsing limit instead of allow for SSH helps prevent brute-force attacks by denying connections to any IP that tried to connect at least 6 times in the last 30 seconds. We also set default policies for incoming connections (denied) and outgoing connections (allowed). This should already be the default configuration, but it doesn’t hurt.

Before enabling the firewall, make sure that you have correctly applied the SSH rule, otherwise you might lock yourself out of your server. It should have shown :

Rules updated

Rules updated (v6)If you are sure, let’s proceed :

# ufw enableCheck that everything looks good :

# ufw status verbose

Status: active

Logging: on (low)

Default: deny (incoming), allow (outgoing), disabled (routed)

New profiles: skip

To Action From

-- ------ ----

22/tcp LIMIT IN Anywhere

22/tcp (v6) LIMIT IN Anywhere (v6)It’s a good idea at this point to open a new terminal window and try to connect again to the server, to make sure that the port is not blocked.

4.9 Automatic system updates

In order for the server to automatically apply upgrades, we’ll install the unattended-upgrades service for apt :

# apt install unattended-upgradesDepending on the system image used by the provider to build the VPS, it might already be installed by default.

We want to receive an email when some updates are installed in order to keep an eye on the server, and we enable logging through syslog :

# nano /etc/apt/apt.conf.d/50unattended-upgrades

Unattended-Upgrade::Mail "root";

Unattended-Upgrade::MailReport "on-change";

Unattended-Upgrade::SyslogEnable "true";

Unattended-Upgrade::SyslogFacility "daemon";These lines must be uncommented, and the mail address is set to “root”. This will send a system email to the root user.

While you are in this file, take the time to look at the other configuration options. For instance, you may want to enable the following settings in order to automatically clean up old kernels and packages after an upgrade :

Unattended-Upgrade::Remove-Unused-Kernel-Packages "true";

Unattended-Upgrade::Remove-Unused-Dependencies "true";You may also want that the server automatically reboots if required by the upgrade :

Unattended-Upgrade::Automatic-Reboot "true";

Unattended-Upgrade::Automatic-Reboot-Time "02:00";Whether or not this is a good idea depends on your use case.

4.10 System emails

Users on a Unix-like system can send each other local emails (I guess this is a relic of the old mainframes back in the day). While I believe this mostly fell out of use, it still is a useful way to receive notifications from automated processes on the system. For example, cron may send emails to root to notify the administrator of the result of the tasks that it launches, and we also configured unattended-upgrades above to send us emails as well when an update is applied.

However, instead of checking the server for the local user emails, it is usually more practical to receive actual emails in our inbox. For this, we will install nullmailer as a simple mailer service that will forward the local root emails to an SMTP server of our choice.

First, we need to create a mailbox (an email address) named root@n1.mydomain.com, that will be used to send these emails. How you do this depends on your email server.

Then we install and configure nullmailer :

# apt install nullmailerThis will ask for the FQDN (Fully-Qualified Domain Name) of the server. Since we configured the hostname earlier it should already be correct, but make sure it is set to n1.mydomain.com.

Next, we enter the SMTP server you would like to send the emails through. The default value will probably be mail.mydomain.com or smtp.mydomain.com, which may be the correct answer, but this depends on your configuration.

Configuring nullmailer requires setting three very simple files. First, the email address that we would like to receive the notifications on (our usual email address) :

# nano /etc/nullmailer/adminaddr

myname@mydomain.comSecond, the domain of this server (make sure it includes the full domain : it might only contain mydomain.com by default) :

# nano /etc/nullmailer/defaultdomain

n1.mydomain.comFinally, the settings of the MTA1 to send the email through. You will need to customize this according to the connection settings of your SMTP server :

# nano /etc/nullmailer/remotes

mail.mydomain.com smtp --port=25 --starttls --user=root@n1.mydomain.com --pass=MyVeryStr0ngMailboxP4sswordWe need to restart nullmailer in order to take this configuration into account :

# systemctl restart nullmailerFinally, we can send a test email to make sure everything is setup correctly :

# echo -e "To: `cat /etc/nullmailer/adminaddr`\nSubject: Test email from `hostname`\n\nThis is a test email sent to root@`hostname` and forwarded to `cat /etc/nullmailer/adminaddr`." | sendmail rootYou should receive an email at the address that you configured in /etc/nullmailer/adminaddr.

1 Mail Transfer Agent : an email server

4.11 Logs

As explained in the introduction, we want to centralize on the main node (N1) the logs of all the nodes. For this, we will use rsyslog to collect the logs each node, forward them to N1 over the network, and organize them in the /logs directory there.

First, we install rsyslog, as well as its openssl module :

# apt install -y rsyslog rsyslog-opensslDebian is based on systemd, which means the system logs are handled by journald, the logging component of systemd. Fortunately, it is easy to configure journald to forward all logs to rsyslog, there is only a single line to uncomment in journald‘s config file :

# nano /etc/systemd/journald.conf

ForwardToSyslog=yesThis is where the setup will be a bit different between N1 and the other nodes. From a logical point of view, in this context N1 will act as an rsyslog “server”, while the other nodes will be “clients”.

4.11.1 Central node (N1)

We will store the logs in a dedicated volume mounted on /logs. After creating the volume (in my case in Gandi’s web interface), we can read the UUID of the partition in order to add the mountpoint to the fstab, then instruct mount to use it :

# blkid

/dev/xvdb1: LABEL="logs" UUID="2f372a95-9193-4727-9a09-a52fb5cff1a7" BLOCK_SIZE="4096" TYPE="ext4"

# nano /etc/fstab

<...>

UUID=2f372a95-9193-4727-9a09-a52fb5cff1a7 /logs ext4 rw,noexec 0 2

# mount -aLogs can be sensitive information and even though we will be sending them over the private network, we want to make sure they are encrypted during the transfer. We also want to authenticate the clients (the other nodes) when they connect, to make sure that a rogue actor or a compromised node won’t impersonate another node and won’t send fake events in the logs (or try to saturate the central node’s storage). The clients will also authenticate the server to make sure they don’t send their logs to a spoofed central node. This is called “mutual TLS”, or mTLS.

For this purpose, we will generate self-signed certificates for the server and the clients and configure rsyslog to transfer data over an encrypted and authenticated TLS connection. The keys and certificates will be stored in /etc/rsyslog.d/keys :

# mkdir /etc/rsyslog.d/keysCA certificate

First, we will generate a CA certificate that will serve as the root of trust for the other certificates. There will only be one CA certificate for the whole network.

We start by creating an RSA keypair :

# openssl genrsa -out /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.key 4096This file contains the private key of the CA. It’s very important to keep it secure, so let’s make sure only root can read it :

# chmod 600 /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.keyWe generate a CA certificate using this keypair that will be valid for 3650 days (10 years) :

# openssl req -x509 -new -noenc -key /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.key -days 3650 -out /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.crt -subj "/CN=n1.mydomain.com"Later, we will need to copy this CA certificate on all the other nodes.

Server’s certificate

Now we create the server’s certificate. Similarly to the CA, we start by generating an RSA keypair :

# openssl genrsa -out /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n1.mydomain.com.key 2048

# chmod 600 /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n1.mydomain.com.keyAs before, make sure to keep it secure.

The server’s certificate needs to be signed by the CA. In order to do this, we start by creating a CSR (Certificate Signing Request) :

# openssl req -new -key /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n1.mydomain.com.key -out /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n1.mydomain.com.csr -subj "/CN=n1.mydomain.com" -addext "subjectAltName = IP:192.168.1.101"Make sure to set the CN (Common Name) correctly, and if you have a private network, add the local IP of the server as a SAN (SubjectAltName). Depending on whether you will connect via the domain name or the direct private network’s IP address, either one of them will be checked against the CN and the SAN during the authentication of the TLS connection.

We then use this CSR to create the actual certificate for the server, with the same SAN, valid for 10 years as well :

# openssl x509 -req -in /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n1.mydomain.com.csr -CA /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.crt -CAkey /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.key -CAcreateserial -days 3650 -copy_extensions copyall -ext subjectAltName -out /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n1.mydomain.com.crtIf everything went well, the CSR is no longer useful and can be removed :

# rm /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n1.mydomain.com.csrTo sum up, we now have :

ca.key: the CA’s private key, that will be used to sign the certificates for the clients laterca.crt: the CA’s certificate, that we will need to distribute to the clients so they are able to authenticate the server’s certificaten1.mydomain.com.key: the server’s private keyn1.mydomain.com.crt: the server’s certificate

rsyslog’s config

We’re done with the certificates. Now, let’s configure rsyslog by creating a new file in /etc/rsyslog.d/10-main.conf with the following content :

# nano /etc/rsyslog.d/10-main.conf

$PreserveFQDN on

module(load="imtcp")

input(type="imtcp"

Address="192.168.1.101"

Port="6514"

PermittedPeer="*.mydomain.com"

StreamDriver.Name="ossl"

StreamDriver.Mode="1"

StreamDriver.AuthMode="x509/name"

StreamDriver.CertFile="/etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n1.mydomain.com.crt"

StreamDriver.KeyFile="/etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n1.mydomain.com.key"

StreamDriver.CAFile="/etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.crt")

$AllowedSender TCP, 127.0.0.1, [::1]/128, 192.168.1.0/24

$template LogDestination,"/logs/%hostname%/%syslogfacility-text%/%programname%.log"

*.* ?LogDestination;RSYSLOG_FileFormat

if ($inputname == 'imuxsock' and not ($syslogfacility-text == 'auth' or $syslogfacility-text == 'authpriv')) then -/var/log/syslog

if ($inputname == 'imuxsock' and ($syslogfacility-text == 'auth' or $syslogfacility-text == 'authpriv')) then /var/log/auth.log

if ($inputname == 'imuxsock' and $syslogfacility-text == 'cron') then -/var/log/cron.log

if ($inputname == 'imuxsock' and $syslogfacility-text == 'kern') then -/var/log/kern.log

if ($inputname == 'imuxsock' and $syslogfacility-text == 'mail') then -/var/log/mail.log

if ($inputname == 'imuxsock' and $syslogfacility-text == 'user') then -/var/log/user.log

if ($inputname == 'imuxsock' and $syslogseverity-text == 'emerg') then :omusrmsg:*

stopThis will instruct rsyslog to listen on port 6514 of the private network’s interface for TLS connections with the certificates that we just created. Don’t forget to change the PermittedPeer setting to match your setup : only the clients that match this value will be able to connect1. I added only localhost and the private network to $AllowedSender, but if you don’t have a private network, specify the IPs of your other nodes there.

The LogDestination2 template defines the file path that the logs will be saved to. Specifying the RSYSLOG_FileFormat3 format helps ensure consistent formatting from the lines coming from the other nodes.

Then, the lines below will make sure that the local logs are still written to the files at their standard location, as expected by some services such as Fail2ban. For this purpose, we filter on the $inputname property : local logs come from the imuxsock (read input module unix socket) module, while remote logs from the the imtcp module that we defined above.

The last instruction of the file, stop, ensures that any other default rule in the main rsyslog config file is ignored to avoid duplicate entries.

Finally, all that’s left to do is to open the port 6514 on the private network in the firewall :

# ufw allow from 192.168.1.0/24 to any port 6514 proto tcpIf you don’t have a private network, simply open the same port globally without specifying an interface : ufw allow 6514 proto tcp.

1 The documentation for these TCP-related settings can be found here : https://www.rsyslog.com/doc/configuration/modules/imtcp.html.

2 Read more about rsyslog properties here : https://www.rsyslog.com/doc/configuration/properties.html.

3 Read more about rsyslog templates here : https://www.rsyslog.com/doc/configuration/templates.html.

4.11.2 Client nodes (N2, N3, …)

First, we need to create the client’s certificate. The process is similar to generating the server’s certificate and signing it using the CA’s private key. On N2, after installing rsyslog :

root@n2.mydomain.com# mkdir /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/We create an RSA keypair :

root@n2.mydomain.com# openssl genrsa -out /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.key 2048Then a CSR (Certificate Signing Request) :

root@n2.mydomain.com# openssl req -new -key /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.key -out /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.csr -subj "/CN=n2.mydomain.com" -addext "subjectAltName = IP:192.168.1.102"We now need to transfer this CSR to the central server (N1) to sign it. For this, we’ll use scp from our local machine :

$ scp root@n2.mydomain.com:/etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.csr root@n1.mydomain.com:/etc/rsyslog.d/keysThen, on N1, we sign this CSR to create a certificate, the same way we did for the server’s certificate :

root@n1.mydomain.com# openssl x509 -req -in /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.csr -CA /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.crt -CAkey /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.key -CAcreateserial -days 3650 -copy_extensions copyall -ext subjectAltName -out /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.crtWe transfer this certificate (n2.mydomain.com.crt) back to N2 :

$ scp root@n1.mydomain.com:/etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.crt root@n2.mydomain.com:/etc/rsyslog.d/keysThe CSR files are not useful anymore and can be deleted :

root@n1.mydomain.com# rm /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.csrroot@n2.mydomain.com# rm /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.csrThe only thing missing is the CA certificate that needs to be copied to N2 :

$ scp root@n1.mydomain.com:/etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.crt root@n2.mydomain.com:/etc/rsyslog.d/keysThat’s it for the certificates on the client. We should have three files in /etc/rsyslog.d/keys :

n2.mydomain.com.key: the client’s private keyn2.mydomain.com.crt: the client’s certificateca.crt: the CA’s certificate, used to authenticate the certificate sent by the server

Finally, we set up the rsyslog configuration. There should already be a configuration file in /etc/rsyslog.conf containing (among other things), these two instructions :

module(load="imuxsock")

module(load="imklog")im‘s are input modules which provide ways for rsyslog to collect log entries. imuxsock listens to a Unix socket (in cooperation with journald1), while imklog collects logs directly from the kernel. At the end of this config file, you will also find the instructions to write these logs into the default system log files : /var/log/syslog, /var/log/auth.log, and so on.

Since we also want to forward the logs to our central node, we need to create a new configuration file :

root@n2.mydomain.com# nano /etc/rsyslog.d/10-main.conf

$PreserveFQDN on

$DefaultNetstreamDriver ossl

$DefaultNetstreamDriverCAFile /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/ca.crt

$DefaultNetstreamDriverCertFile /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.crt

$DefaultNetstreamDriverKeyFile /etc/rsyslog.d/keys/n2.mydomain.com.key

$ActionSendStreamDriverAuthMode x509/name

$ActionSendStreamDriverPermittedPeer n1.mydomain.com

$ActionSendStreamDriverMode 1

*.* @@(o)192.168.1.101:6514;RSYSLOG_ForwardFormatThis instructs the rsyslog instance on the client side to forward all logs (“*.*“) to 192.168.1.101 (N1‘s private IP) on port 6514, via TCP with TLS (“@@(o)“). Don’t forget to change the CertFile and KeyFile, as well as the PermittedPeer. The setting “AuthMode x509/name” instructs the driver to check that the CN and SAN in the certificate matches the server’s hostname or IP, and DriverMode 1 forces rsyslog to use a TLS connection. Forcing the RSYSLOG_ForwardFormat formats ensure that the format of the timestamp will be consistent across all nodes and include microsecond precision, which may be useful for troubleshooting some issues.

1 https://www.rsyslog.com/doc/configuration/modules/imuxsock.html#coexistence-with-systemd

Then, for both the central nodes and the other nodes, we now only need to restart rsyslog and journald to take into account the new configuration :

# systemctl restart rsyslog

# systemctl restart systemd-journaldMake sure there is no configuration or connection error :

# systemctl status rsyslogAfter a while, in /logs on N1, you should see directories for both nodes :

# ls /logs

n1.mydomain.com n2.mydomain.com

# ls /logs/n1.mydomain.com

auth authpriv daemon kern syslog

# ls /logs/n2.mydomain.com

auth daemon kern syslogThe subdirectories for the nodes and the facilities are created on-demand. If you don’t see anything, you can manually log something as a test :

root@n2.mydomain.com# logger Testroot@n1.mydomain.com# cat /logs/n2.mydomain.com/user/root.log

2025-04-17T18:18:41.802577+02:00 n2.mydomain.com root TestGreat ! It was a big chunk, but we now have centralized aggregation of the logs of our nodes !

Look at these two sections to go further :

4.11.4 Logrotate

logrotate is used to automatically archive and compress log files after a specified time or when they reach a specified size. Make sure it is installed :

# apt install logrotateMost system services already provide a configuration for logrotate to rotate their own logs. However, on N1, we need to create a configuration file to instruct logrotate to rotate the remote logs in /logs :

# nano /etc/logrotate.d/remote_logs

/logs/*/*/*.log

{

rotate 4

weekly

size 100M

missingok

notifempty

compress

delaycompress

sharedscripts

postrotate

/usr/lib/rsyslog/rsyslog-rotate

endscript

}Take a look at man logrotate to read more about the individual settings.

There is no need to restart anything : logrotate is not a daemon, it’s a simple program that runs everyday on a timer. The new configuration file will be taken into account at the next run.

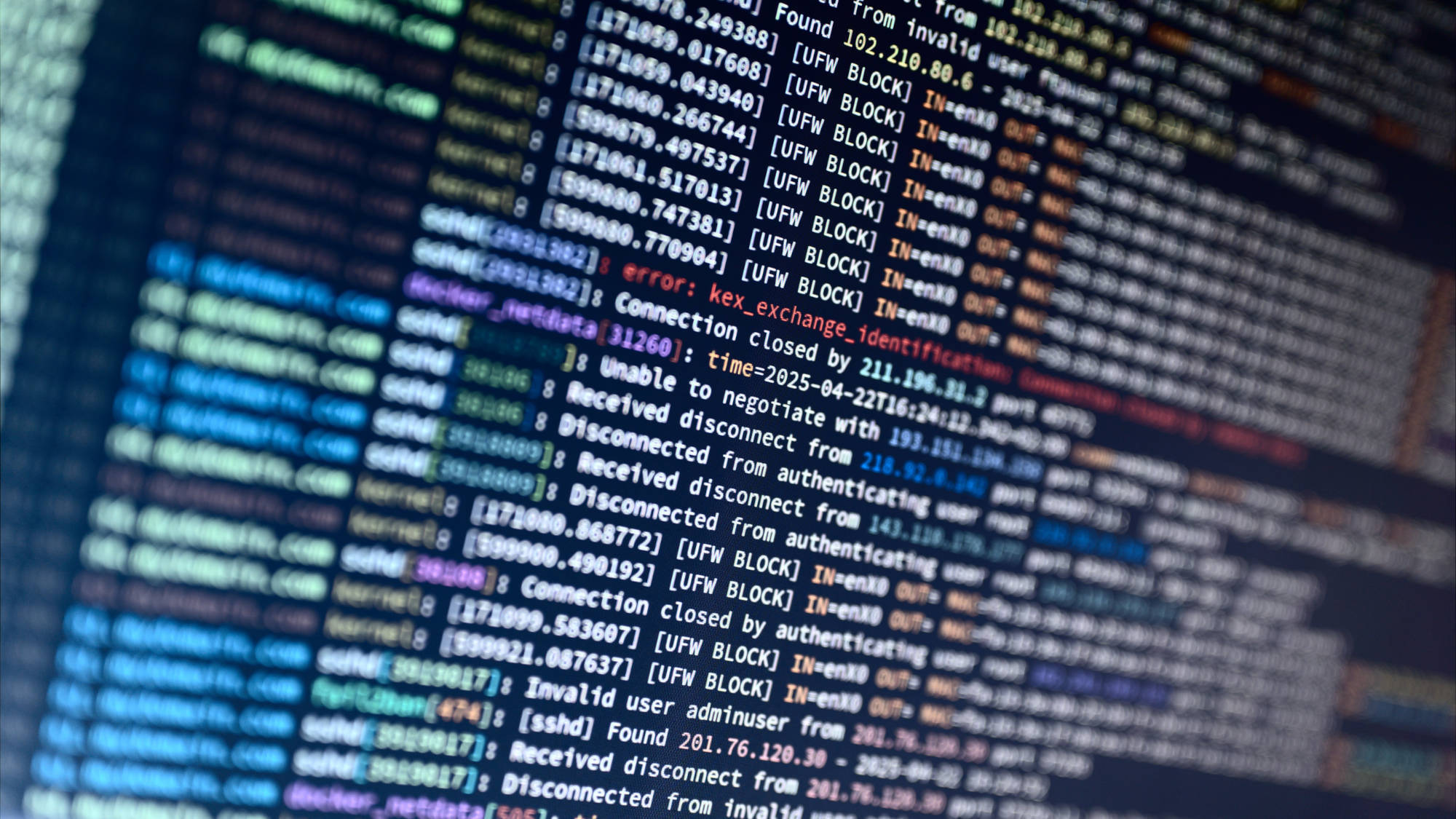

4.12 Fail2ban

The internet is a dangerous place (it should be called the World Wild Web really), and as soon as your server is online, it will attract a horde of bots trying to force access, especially through SSH. Even though we disabled password login and limited the port in the firewall, it’s still a good idea to add another layer of protection. This can be done using fail2ban : this tool will watch the logs of the services you instruct it to, check for repeated connection attempts from the same IPs, and block (“ban”) them using ufw when then reach a configured threshold. It’s not just for SSH : fail2ban can watch any service that you configure it to. For example, it could block IPs attempting to bruteforce the WordPress login page by watching your webserver’s logs.

First, let’s install fail2ban :

# apt install fail2banConfigurations files are in /etc/fail2ban. Do not edit the fail2ban.conf and jail.conf files directly : instead, create a fail2ban.local file for global settings and a jail.local for “jails” settings1. However, feel free to read the fail2ban.conf file to understand what the settings mean.

In the global settings, we will only change the logtarget parameter to tell fail2ban to send its activity log to systemd (which will in turn forward it to rsyslog) :

# nano /etc/fail2ban/fail2ban.local

[DEFAULT]

logtarget = SYSTEMD-JOURNALAnd in the jails configuration file, we will enable the monitoring of SSH connection attempts :

# nano /etc/fail2ban/jail.local

[sshd]

enabled = true

port = ssh

filter = sshd

action = ufw

logpath = %(sshd_log)s

backend = systemd

maxretry = 4

bantime = 24h

findtime = 1hIn this case, any IP that makes 4 failed connection attempts in a 1-hour window will be blocked for 24 hours. Feel free to customize this to suit your needs.

Read more about proper fail2ban configuration here : https://github.com/fail2ban/fail2ban/wiki/Proper-fail2ban-configuration.

Reload fail2ban to apply this configuration, and check that everything looks right :

# systemctl restart fail2ban

# systemctl status fail2banFail2ban can be operated using the provided fail2ban-client command. Here are a few useful commands :

fail2ban-client banned: shows the list of IPs banned for each jailfail2ban-client unban X.X.X.X: unblock an IP

1 A “jail” is the configuration to protect a specific service.

4.13 Logcheck

This applies only to the central node, N1.

If you don’t plan on spending your days looking at your server logs, some important alerts (something not working well, or someone trying to do something fishy) might go unnoticed. Fortunately, there is an alternative : logcheck is a simple tool that runs on a cron timer, reads all the logs for you, checks them against a database of regex rules, and sends you a report via email if it finds something unusual. While it takes some time to get things right when configuring it, it’s a valuable tool to keep an eye on your servers. Let’s add it to our toolbelt.

Since all the logs are centralized on N1, we only need to install logcheck once, on this node, in order to monitor our whole infrastructure.

# apt install logcheckThis will install both logcheck, the parser itself, and logcheck-database, which contains a community-maintained list of rules that will help you get started.

Main configuration

The cron task that logcheck runs on is defined in /etc/cron.d/logcheck. At the time of this writing, the default for the Debian package appears to be to run it on @reboot and on 2 * * * *, which means every hour at 2 after the dot, and every time after a reboot. If you want to customize this to run it more or less frequently, now is the time by editing this file.

Let’s edit the main config file :

# vim /etc/logcheck/logcheck.conf

REPORTLEVEL="server"

SENDMAILTO="root"

MAILASATTACH=0

FQDN=1

ADDTAG="yes"The report emails will be sent to the root user, which are now redirected to our email address thanks to nullmailer. Set MAILASATTACH to 1 if you want the report to be included as an attachment instead of directly into the body of the email. ADDTAG is used to place a [logcheck] tag in the subject line of the emails, which make it easier to sort these emails using message filters.

We’ll now tell logcheck where the logs we want it to parse are. By default, it reads from journald, /var/log/syslog and /var/log/auth.log. In our case, we want it to read from the logs sorted into /logs, so we need to comment the default sources and add a new one :

# vim /etc/logcheck/logcheck.logfiles.d/journal.logfiles

#journal

# vim /etc/logcheck/logcheck.logfiles.d/syslog.logfiles

#/var/log/syslog

#/var/log/auth.log

# vim /etc/logcheck/logcheck.logfiles.d/aggregated_syslog.logfiles

/logs/*/*/*.log

logcheck will therefore read the log files for every process and every facility of every node.

Rules

Now, we need to configure the regex rules that logcheck will use to determine if a log line is benign or not. These rules are defined in the xxx.d subdirectories in /etc/logcheck/. The documentation is available here :

# zless /usr/share/doc/logcheck-database/README.logcheck-database.gzBasically, there are three alert levels : security alerts (cracking), security events (violations), and system events (everything else). Each line in a rules file simply defines a regex to check. The rules in cracking.d/ and violations.d/ are positive, meaning a match triggers an alert of the corresponding level. The rules in cracking.ignore.d/ and violations.ignore.d/ are negative and are used override these alerts. Most importantly : every line that is not considered a security alert or security event according to these rules is considered to be a system event by default, and is checked against the rules in ignore.d.server/1. Every line that is not explicitely ignored by a rule is reported, and by default there will probably a lot of false-positive reported by logcheck, so this is the directory where you will need to spend some time if you don’t want to be flooded with notifications.

Configuring the rules is a bit of a whack-a-mole game : find a false-positive, write the rule to eliminate it, and another false-positive will pop. It’s a bit of work, but after a while the number of false-positive in the reports will decrease exponentially, and it’s worth the work.

Here is the process that I recommend :

- Check which log lines are reported by

logcheckusing its test mode :# sudo -u logcheck logcheck -o -t - Take a single line that looks like a benign event you want to ignore, for example :

2025-04-21T16:41:06.016960+02:00 n1.mydomain.com fail2ban[474]: [sshd] Ban X.X.X.X - Copy it to regex101, a very useful tool to develop and debug regex’s

- Look for a rules file for this service that would already exist in

/etc/logcheck/ignore.d.server/: for example, there is already a file forsshwhich we can customize, but not forfail2ban. Let’s create it :# vim /etc/logcheck/ignore.d.server/fail2ban - Look around in the rules files for a regex that matches a similar line (especially up to the process id field in brackets), copy it to regex101, and tweak it until it matches your log line :

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ fail2ban[[[:digit:]]+]: [[[:alnum:]]+] (B|Unb)an [:[:xdigit:].]+$2 - Add the regex to your rules file, and start again at step 1 by running

logcheckagain to check whether it has eliminated this line and similar ones from the report.

1 There are three reporting levels depending on your requirements : workstation, server and paranoid. We set REPORTLEVEL to “server” in the main config file, so logcheck will read the rules from ignore.d.server/.

2 The $ sign at the end of the regex is important : it defines whether this should match against the whole line, or only the beginning. Most of the time, you will want to write regex’s that match against the whole line (and therefore do have a dollar sign at the end), to be as explicit as possible. Though in some cases, an open-ended regex can be enough when the end of a specific log event can take a lot of different forms.

Sometimes, you will find a log line that is supposed to be ignored by a rule, but doesn’t match exactly because an update to that particular program has slightly changed the format of the message. I find that this occurs a lot with sshd in my case. As a reference, here are a few rules that I added or updated for my setup, feel free to copy and adapt them to your needs.

Custom rules

/etc/logcheck/ignore.d.server/ssh

Updated :

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: Connection (closed|reset) by( (invalid|authenticating) user [^[:space:]]*)? [:.[:xdigit:]]+ port [[:digit:]]{1,5}( \[preauth\])?$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: Received disconnect from [:[:xdigit:].]+(:| port) ([[:digit:]]+:){1,2} .{0,256} \[preauth\]$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: Disconnecting( (authenticating|invalid) user [^[:space:]]* [:[:xdigit:].]+ port [[:digit:]]+)?: Too many authentication failures (for [^[:space:]]* )?\[preauth\]$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: Disconnected from( (invalid|authenticating))?( user [^[:space:]]*)? [:[:xdigit:].]+ port [[:digit:]]{1,5}( \[preauth\])?$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: (Disconnecting: )?Corrupted MAC on input\.( \[preauth\])?$Added :

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: (error: (kex_exchange_identification|kex_protocol_error)|banner exchange):

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: error: maximum authentication attempts exceeded for (invalid user )?[._[:alnum:]-]+ from [:[:xdigit:].]+(:| port) ([[:digit:]]+:?){1,2} .{0,256} \[preauth\]$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: Unable to negotiate with [:[:xdigit:].]+ port [[:digit:]]+: no matching (host key type|key exchange method) found.( Their offer: [^[:space:]]*)?( \[preauth\])?$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: userauth_pubkey: signature algorithm ssh-rsa not in PubkeyAcceptedAlgorithms \[preauth\]$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: pam_env\(sshd:session\): deprecated reading of user environment enabled$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: fatal: userauth_pubkey: parse publickey packet: incomplete message \[preauth\]$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: error: Protocol major versions differ: [[:digit:]] vs\. [[:digit:]]$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ sshd\[[[:digit:]]+\]: ssh_dispatch_run_fatal: Connection from [:[:xdigit:].]+ port [[:digit:]]{1,5}: message authentication code incorrect \[preauth\]$ /etc/logcheck/ignore.d.server/systemd

^([[:alpha:]]{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ systemd\[[0-9]+\]: Activating special unit exit\.target\.\.\.$ /etc/logcheck/ignore.d.server/ufw

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ kernel: \[[\.[:digit:]]+\] \[UFW (LIMIT )?BLOCK\] /etc/logcheck/ignore.d.server/fail2ban

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ fail2ban\[[[:digit:]]+\]: \[[[:alnum:]]+\] Found [:[:xdigit:].]+ - [0-9]{4}-[0-9]{2}-[0-9]{2} [0-9]{2}:[0-9]{2}:[0-9]{2}$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ fail2ban\[[[:digit:]]+\]: \[[[:alnum:]]+\] (B|Unb)an [:[:xdigit:].]+$ /etc/logcheck/ignore.d.server/unattended-upgrades

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ unattended-upgrade(\[[[:digit:]]+\])?: Enabled logging to syslog via daemon facility$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ unattended-upgrade(\[[[:digit:]]+\])?: Checking if system is running on battery is skipped. Please install powermgmt-base package to check power status and skip installing updates when the system is running on battery\.$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ unattended-upgrade(\[[[:digit:]]+\])?: Checking if connection is metered is skipped. Please install python3-gi package to detect metered connections and skip downloading updates\.$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ unattended-upgrade(\[[[:digit:]]+\])?: Starting unattended upgrades script$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ unattended-upgrade(\[[[:digit:]]+\])?: Initial blacklist:

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ unattended-upgrade(\[[[:digit:]]+\])?: Initial whitelist \(not strict\):

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ unattended-upgrade(\[[[:digit:]]+\])?: Allowed origins are:( origin=[[:alnum:]_\-\.]+,codename=[[:alnum:]_\-\.]+,label=[[:alnum:]_\-\.]+,?)+

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ unattended-upgrade(\[[[:digit:]]+\])?: No packages found that can be upgraded unattended and no pending auto-removals$ /etc/logcheck/ignore.d.server/nullmailer

Updated :

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ nullmailer-send\[[0-9]+\]: Rescanning queue\.

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ nullmailer-send\[[0-9]+\]: Trigger pulled\.

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ nullmailer-send\[[0-9]+\]: Starting delivery, [0-9]+ message\(s\) in queue\.

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ nullmailer-send\[[0-9]+\]: Starting delivery: host: .+ protocol: [a-z]+ file: [0-9\.]+

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ nullmailer-send\[[0-9]+\]: Sent file\.

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ nullmailer-send\[[0-9]+\]: Delivery complete, 0 message\(s\) remain\.

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ nullmailer-send\[[0-9]+\]: smtp: Succeeded:Added :

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ nullmailer-send\[[0-9]+\]: From: <[[:alnum:]_\-\.@]+> to: <[[:alnum:]_\-\.@]+>$

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ nullmailer-send\[[0-9]+\]: Message-Id: <[[:alnum:]_\-\.@]+>$ The services running inside Docker containers (which we will configure later) may generate tons of logs that are irrelevant from a security standpoint. If you want to ignore them all, here is a rule that will filter every process that starts with docker_.

/etc/logcheck/ignore.d.server/docker

^(\w{3} [ :[:digit:]]{11}|[0-9T:.+-]{32}) [._[:alnum:]-]+ docker_[[:alnum:]_\-\.]+\[[[:digit:]]+\]:If you want to be more selective, you can specify the container names individually. Or, if you only want to monitor for specific events from the containers to trigger an alert, you can define them in violations.d/or cracking.d/.

Now that everything is setup, it’s a good idea to spend a few minutes looking at the logs to make sure everything looks right :

$ lnav "root@n1.mydomain.com:/logs/*/*"You should see events from all your nodes, including probably :

- Some failed SSH connection attempts :

n1.mydomain.com sshd[xxxxxxx]: Invalid user guest from X.X.X.X port X - Fail2ban doings its job :

n3.mydomain.com fail2ban[xxxxxx] [sshd] Found X.X.X.X - The firewall blocking connections :

kernel [UFW BLOCK] ...

That’s it for the system’s configuration ! Take a break, stretch your legs, before diving into the last part : installing Docker and running services inside containers.

5 Docker

In order to make things simpler to manage and to move around, all the Docker services will be centralized in /srv, with a dedicated subdirectory for each service containing at least a docker-compose.yml definition file for that particular service, as well as the persistent volumes, Dockerfile, or any other resource necessary. A global docker-compose.yml file in /srv will simply include each subdirectory, making it easy to add or remove a service : a single line needs to be added or removed (or commented).

5.1 Installation

Installing Docker on Debian is explained well in the official documentation : https://docs.docker.com/engine/install/debian

Here is what I did :

apt update

apt install ca-certificates curl

install -m 0755 -d /etc/apt/keyrings

curl -fsSL https://download.docker.com/linux/debian/gpg -o /etc/apt/keyrings/docker.asc

chmod a+r /etc/apt/keyrings/docker.asc

echo "deb [arch=$(dpkg --print-architecture) signed-by=/etc/apt/keyrings/docker.asc] https://download.docker.com/linux/debian $(. /etc/os-release && echo "$VERSION_CODENAME") stable" | tee /etc/apt/sources.list.d/docker.list > /dev/null

apt update

apt install docker-ce docker-ce-cli containerd.io docker-buildx-plugin docker-compose-plugin5.2 Environment variables

The first file that we’ll create will define some global environment variables that we’ll use inside the docker-compose files. It will make it easier to port them from one node to another.

# cd /srv

# nano .env

BASE_DOMAIN=mydomain.com

NODE_NAME=n1

NODE_HOSTNAME=${NODE_NAME}.${BASE_DOMAIN}

NODE_PRIVATE_IP=192.168.1.101When deploying a new node, remember to customize this file. Ideally, the docker-compose files themselves will stay identical.

Read more about Docker Compose variables interpolation here : https://docs.docker.com/compose/how-tos/environment-variables/variable-interpolation/.

5.3 Internal services

We’ll install two services that will be common to all nodes and serve as a basis for the other services : Traefik as a front-end proxy, and Portainer to centralize management of the services on all nodes. As always, customize to your needs.

5.2.1 Traefik

Traefik is a reverse-proxy that works especially well with Docker. It listens on the HTTP (80) and HTTPS (443) ports, and route the requests to the appropriate container depending on the URL that the user is trying to access. It can automatically request and renew Let’s Encrypt certificates, and the routes are configured directly in each container’s docker-compose.yml definition file, both of which are very handy.

Read more about Traefik on Docker Hub.

Definition file

Let’s create the subdirectory for Traefik and start with the docker-compose file :

# mkdir /srv/traefik

# nano /srv/traefik/docker-compose.yml

services:

traefik:

image: traefik:3

container_name: traefik

restart: unless-stopped

healthcheck:

test: ["CMD", "traefik", "healthcheck"]

ports:

- "80:80"

- "443:443"

environment:

- TZ=Europe/Paris

labels:

- "traefik.http.routers.dashboard.rule=Host(`traefik.${NODE_HOSTNAME}`) && (PathPrefix(`/api`) || PathPrefix(`/dashboard`))"

- "traefik.http.routers.dashboard.tls=true"

- "traefik.http.routers.dashboard.tls.certresolver=letsencrypt"

- "traefik.http.routers.dashboard.service=api@internal"

- "traefik.http.routers.dashboard.middlewares=dashboard-auth"

- "traefik.http.middlewares.dashboard-auth.digestauth.users=myuser:traefik:9594006aaaea8c0b0f9bd13d7bbc34cc"

volumes:

- ./traefik.yml:/etc/traefik/traefik.yml:ro

- ./acme.json:/etc/traefik/acme.json

- /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock

logging:

driver: "syslog"

options:

syslog-facility: "user"

tag: "docker_{{.Name}}"That’s a lot, but if you are familiar with Docker Compose, it should look familiar. Let’s go over some of the important parts :

healthcheck: defines a command inside the container that Docker will run automatically at regular interval to report whether the service is running properly. Check the documentation for thetraefik healthcheckcommand and the docker-compose healthcheck definition.ports: exposes ports from inside the container to the public network interface. Traefik will be the only web service exposing the 80 and 443 ports using this definition statement, it will route traffic to the other services internally.labels: Traefik can be configured directly inside docker-compose files using labels. As we’ll see later, this is how we will connect the other services to the front-end. Here, we added rules to expose a dashboard on thetraefik.mydomain.comsub-domain (using the variable defined in.env), in the/dashboard/subpath. If you don’t want this dashboard, you can delete this part.tls=trueandtls.certresolver=letsencryptinstruct Traefik to automatically manage an HTTPS certificate fortraefik.mydomain.com.middlewares=dashboard-authdefines a new DigestAuth middleware nameddashboard-auth(this is an arbitrary name) that will be used to request authentication from the user before accessing the dashboard. This middleware is configured withmiddlewares.dashboard-auth.digestauth.users=<...>. The digest can be generated usinghtdigestfrom theapache2-utilspackage :# apt install apache2-utils# htdigest -c pw.txt traefik myuser# cat pw.txtmyuser:traefik:9594006aaaea8c0b0f9bd13d7bbc34cc# rm pw

volumes: we mount 3 files inside the container :traefik.yml: the main config file that we will create belowacme.json: the file into which Traefik will store the Let’s Encrypt certificatesdocker.sock: the main socket used to access the Docker API, Traefik needs it to monitor when new services start and read theirlabels.

logging: tells Docker to send the logs of this container to syslog, i.e. the local rsyslog daemon that we configured earlier. All the containers will have the same configuration, which will store the logs of this container into/logs/n<X>.mydomain.com/user/docker_<container-name>.log. For instance :/logs/n1.mydomain.com/user/docker_traefik.log.

Warning : in syslog, by default, the total length of the tag (which includes the process name, process ID, and the colon character) is limited to 32 characters by default.1 If the tag specified in the docker-compose definition file is too long (because the container’s name is too long), the PID and colon might get dropped, which might cause issues with logs parsing. Taking into account the “docker_“prefix, that means we should limit the container’s name to around 15 characters.

1 https://www.rsyslog.com/sende-messages-with-tags-larger-than-32-characters/

Since we enabled the dashboard, we need to create the DNS configuration for mydomain.com, defined as a simple CNAME pointing on the same server :

traefik.n1 10800 IN CNAME n1Traefik’s main config file

# nano /srv/traefik/traefik.yml

entryPoints:

web:

address: ":80"

http:

redirections:

entryPoint:

to: websecure

permanent: true

websecure:

address: ":443"

providers:

docker:

exposedByDefault: true

certificatesResolvers:

letsencrypt:

acme:

email: "myuser@mydomain.com"

storage: "/etc/traefik/acme.json"

tlsChallenge: {}

log:

level: INFO

accessLog: {}

api: {}

ping: {}Most settings should be self-explainatory :

entrypoints: open the 80 and 443 ports, for HTTP and HTTPS respectively, and redirect HTTP to HTTPS.certificatesResolvers: defines the Let’s Encrypt resolver that will be used to generate HTTPS certificates. Don’t forget to specify a valid email address.accessLog: output Traefik’s access log (incoming HTTP requests) onstdout, to be captured by Docker and transfered torsyslog.api: required for the dashboard. If you don’t don’t want to use the dashboard, you can disable it usingdashboard: false.

Certificates file

Traefik stores the certificates it requests into the acme.json file. We just need to create an empty file, otherwise by default Docker will create a directory :

# touch /srv/traefik/acme.json

# chmod 600 /srv/traefik/acme.json Do not forget to chmod it to 600, otherwise Traefik will not accept to use it !

5.2.2 Portainer

Portainer is a web interface used to manage and monitor Docker containers. Through this UI we can restart services, access logs, and even connect to a terminal inside the container. It’s a useful tool if you are more comfortable with a UI or if you want to give other people restricted access to manage some services.

Read more about Portainer on Docker Hub.

Main instance

On N1, we run the main Portainer instance :

root@n1.mydomain.com# mkdir /srv/portainer

root@n1.mydomain.com# nano /srv/portainer/docker-compose.yml

services:

portainer:

image: portainer/portainer-ce:alpine

container_name: portainer

restart: unless-stopped

labels:

- "traefik.http.routers.portainer.rule=Host(`portainer.${BASE_DOMAIN}`)"

- "traefik.http.routers.portainer.tls=true"

- "traefik.http.routers.portainer.tls.certresolver=letsencrypt"

- "traefik.http.services.portainer-srv.loadbalancer.server.port=9000"

volumes:

- ./data:/data

- /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock

logging:

driver: "syslog"

options:

syslog-facility: "user"

tag: "docker_{{.Name}}"Notice that we didn’t define a ports section : instead, we added labels to configure Traefik to route the requests on portainer.mydomain.com to this container on port 9000, and to automatically create a Let’s Encrypt certificate for it. Again, we need to configure the subdomain in the DNS config of mydomain.com :

portainer 10800 IN CNAME n1Requesting the certificate may take a minute or two, if you get a “self-signed certificate” error from your browser when trying to open https://portainer.mydomain.com, wait for a bit and try again.

Agents

On the other nodes, we run Portainer Agent which will allow managing the services on all the nodes from the central Portainer instance on N1 :

root@n2.mydomain.com# mkdir /srv/portainer_agent

root@n2.mydomain.com# nano /srv/portainer_agent/docker-compose.yml

services:

portainer_agent:

image: portainer/agent:latest

container_name: portainer_agent

restart: unless-stopped

ports:

- "${NODE_PRIVATE_IP}:9001:9001"

volumes:

- /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock

- /var/lib/docker/volumes:/var/lib/docker/volumes

labels:

- "traefik.enable=false"

logging:

driver: "syslog"

options:

syslog-facility: "user"

tag: "docker_{{.Name}}"Portainer communicates with its agents through port 9001. To make sure this port is not exposed to the outside world, we open it only on the private network’s interface by specifying the IP of this interface.

The connections between the central Portainer instance and its agents are created through the UI, so we will need to configure this later once the services are started.

5.4 User-facing services

As an example of an external service to run with Docker, we will install a WordPress website. This requires a database, so we’ll install a MariaDB server as well. And for good measure, we’ll also add a PHPMyAdmin interface.

5.4.1 MariaDB

Read more about the MariaDB image on Docker Hub.

We start by creating a directory to store our “secret” files, such as the root password for MariaDB :

# cd /srv

# mkdir .secrets

# chmod 700 .secretsWe change its permissions to 700 to make sure regular users cannot read it.

We can generate a strong password using pwgen :

# apt install pwgen

# pwgen 32 1 > .secrets/mariadb-rootThen, we define the docker-compose config file :

# mkdir mariadb

# nano mariadb/docker-compose.yml

services:

mariadb:

image: mariadb

container_name: mariadb

restart: unless-stopped

labels:

- "traefik.enable=false"

volumes:

- ./data:/var/lib/mysql

- ./conf.d:/etc/mysql/conf.d

- ../.secrets/mariadb-root:/run/secrets/mariadb-root:ro

environment:

- MARIADB_ROOT_PASSWORD_FILE=/run/secrets/mariadb-root

logging:

driver: "syslog"

options:

syslog-facility: "user"

tag: "docker_{{.Name}}"Since this container will not be directly exposed, we don’t define a ports section, and we disable Traefik routing. We also mount into the container the .secrets/mariadb-root that we just created, as well as a persistent data/ directory that will store the databases. Finally, we add the same logging section as all our services to ship the container’s log to rsyslog.

5.4.2 PHPMyAdmin

Read more about the PHPMyAdmin image on Docker Hub.

PHPMyAdmin will allow us to manage the MariaDB databases through a web interface, which will come in handy. Let’s create its docker-compose file :

# mkdir phpmyadmin

# nano phpmyadmin/docker-compose.yml

services:

phpmyadmin:

image: phpmyadmin:latest

container_name: phpmyadmin

restart: unless-stopped

depends_on:

- mariadb

labels:

- "traefik.http.routers.phpmyadmin.rule=Host(`phpmyadmin.${NODE_HOSTNAME}`)"

- "traefik.http.routers.phpmyadmin.tls=true"

- "traefik.http.routers.phpmyadmin.tls.certresolver=letsencrypt"

environment:

- PMA_HOST=mariadb

- PMA_ABSOLUTE_URI=https://phpmyadmin.${NODE_HOSTNAME}/

logging:

driver: "syslog"

options:

syslog-facility: "user"

tag: "docker_{{.Name}}"The PMA_HOST variable will tell PHPMyAdmin to connect to the mariadb container inside the default internal network created by Docker.

The only thing left to do is to create the subdomain pointing to the current node :

phpmyadmin.n2 10800 IN CNAME n2Once the container is started, PHPMyAdmin will be available at https://phpmyadmin.n2.mydomain.com/.

5.4.3 WordPress

Read more about the WordPress image on Docker Hub.

Finally, we install WordPress. First, we create the database password secret file :

# pwgen 32 1 > .secrets/mariadb-wordpressThen the docker-compose file :

# mkdir wordpress

# nano wordpress/docker-compose.yml

services:

wordpress:

image: wordpress:latest

container_name: wordpress

restart: unless-stopped

depends_on:

- mariadb

labels:

- "traefik.http.routers.wordpress.rule=Host(`${BASE_DOMAIN}`) || Host(`www.${BASE_DOMAIN}`)`)"

- "traefik.http.routers.wordpress.tls=true"

- "traefik.http.routers.wordpress.tls.certresolver=letsencrypt"

volumes:

- ./data:/var/www/html

- ./wp-content:/var/www/html/wp-content

- ../.secrets/mariadb-wordpress:/run/secrets/mariadb-wordpress:ro

environment:

- WORDPRESS_DB_HOST=mariadb

- WORDPRESS_DB_USER=wordpress

- WORDPRESS_DB_PASSWORD_FILE=/run/secrets/mariadb-wordpress

- WORDPRESS_DB_NAME=wordpress

logging:

driver: "syslog"

options:

syslog-facility: "user"

tag: "docker_{{.Name}}"5.4.4 Monitoring Docker services with Fail2Ban

Fail2ban requires special attention in order to work with Docker services, for a few reasons :

- The log files will usually not be where Fail2ban expects them by default (or even exist at all, if Docker collects the logs from the

stdoutof its services, and sends them torsyslogwhich directly forwards them externally). - These operations might change the formats of the logs or prefix the entries with additional data, compared to what the regex’s of the default Fail2ban filters expect, so malicious entries may not be properly detected.

- Due to the way routing works inside Docker’s virtual networks, the default firewall (we configured

ufwhere) might be bypassed entirely, and even if Fail2ban detects malicious connections and tries to block them, these directives might be ignored.1

The third issue, regarding properly blocking traffic, is easy to work around : we simply need to tell Fail2ban to block the connections in the appropriate route by specifying chain = DOCKER-USER in the jail’s config.2

The first issue, regarding log files, has multiple solutions :

- We could mount a persistent file in our service’s

docker-compose.ymland configure the service to log to this file. However, this usually means that the logs won’t be collected by Docker anymore, because most services don’t have the option to log to bothstdoutand a file (Traefik doesn’t, for instance3). This is not recommended. - We could create a special config in

rsyslogto send the logs of the services we want to monitor in a dedicated file, that Fail2ban will read. For instance, here is an instruction that could be added to/etc/rsyslog.d/10-main.confto send a copy of Traefik’s access logs to/var/log/traefik.log:if ($programname == 'docker_traefik') then -/var/log/traefik.log

However this uses twice the disk space for these entries, and we need to make sure that these logs are rotated properly withlogrotate. - Or, we could simply read from the main syslog file at

/var/log/syslog, provided the regex’s are designed to specifically target only the log entries related to the service we are interested in.

Finally, the second issue, regarding log formats, can be solved either by creating our own Fail2ban filters that takes Rsyslog’s encapsulation into account, or by making sure the logs are written in their original format.

As an example, let’s say we want to protect all our web services against bots trying to discover sensitive information. In my case, I get a lot of traffic trying their luck to read some .env files from my websites, so we’ll setup Fail2ban to block these requests before they reach our Traefik frontend proxy. We’ll use the second approach above as it offers a good compromise.

So, we need to give Fail2ban access to the relevant logs. For this, we configure Rsyslog to send Traefik’s log entries to /var/log/traefik.log by adding this configuration at the end of /etc/rsyslog.d/10-main.conf :

set $.trimmedmsg = ltrim($msg);

template(name="RawMsg" type="list") {

property(name="$.trimmedmsg" droplastlf="on")

constant(value="\n")

}

if ($programname == 'docker_traefik') then action(type="omfile" file="/var/log/traefik.log" template="RawMsg")This creates a custom template4 named RawMsg that only contains the raw original message coming from the container (not the timestamp, hostname and process id that Rsyslog usually prefixes to the line), trimmed of any space character at the start5. Every log entry that have a programname set to docker_traefik will be written to /var/log/traefik.log using this template.

Then, we create a custom filter for Fail2ban named “traefik” that matches any GET or POST request to an URL that starts with /.env :

# nano /etc/fail2ban/filter.d/traefik.conf

[Definition]

failregex = ^<HOST> \S+ \S+ \[[^\]]*\] \"(GET|POST) \/\.env\S* HTTP\/[^\"]+\" \d+ \d+ \"[^\"]+\" \"[^\"]+\" \d+ \"\w+@docker\" \"[^\"]+\" \d+ms\s*$

ignoreregex =And we add a jail that uses this filter at the end of jail.local :

# nano /etc/fail2ban/jail.local

<... existing jails ...>

[traefik]

enabled = true

filter = traefik

logpath = /var/log/traefik.log

port = http,https

chain = DOCKER-USER

maxretry = 1

bantime = 24hThe important part here is that instead of action=ufw we set chain=DOCKER-USER to block the traffic using the correct routing chain used by Docker.

Then, we should define a logrotate configuration to handle this file :

# nano /etc/logrotate.d/traefik

/var/log/traefik.log {

weekly

rotate 1

missingok

}And finally, restart rsyslog and fail2ban to load this new configuration :

# systemctl restart rsyslog

# systemctl restart fail2banThis is a simple example to illustrate the process. Use it to create the filters relevant to your use case by customizing the failregex. Here is the documentation that describes how to write proper filters : https://fail2ban.readthedocs.io/en/latest/filters.html.

1 https://docs.docker.com/engine/network/packet-filtering-firewalls/#docker-and-ufw

2 https://github.com/fail2ban/fail2ban/wiki/Fail2Ban-and-Docker

3 https://doc.traefik.io/traefik/observability/access-logs/#filepath

4 https://www.rsyslog.com/doc/configuration/templates.html

5 https://www.rsyslog.com/doc/rainerscript/functions/rs-trim.html

If you want to read more about best practices for Docker containers security, take a look at this article : https://www.linuxserver.io/blog/docker-security-practices.

5.5 Main docker-compose file

Now that we have some services to run, we only need a parent docker-compose.yml to aggregate and run them. For N1, this will look like :

name: n1

include:

- traefik/docker-compose.yml

- portainer/docker-compose.ymlOn the other nodes, this may look like :

name: n2

include:

- portainer_agent/docker-compose.yml

- traefik/docker-compose.yml

- mariadb/docker-compose.yml

- phpmyadmin/docker-compose.yml

- wordpress/docker-compose.ymlThat’s it : we simply define the name of the node for this “Docker Compose project” (Portainer will use it in its UI), and include the services.

Let’s start the containers :

# docker compose up -dAnd check that everything looks right :

# docker compose logs -fIf you have installed a WordPress instance, do not wait long to finish its installation as it currently sits unprotected and will soon attracts bots.

Final configuration

Now that the containers are online, we can put the final touches to our setup.

Portainer

Head to https://portainer.mydomain.com/ and finish any installation required. Then, for each node other than N1 :

- in the left menu, go to Environment-related > Environments and click on Add environment,

- select Docker Standalone, and click on Start Wizard,

- set Name to the hostname of the node (

n2.mydomain.com), and Environment address to the IP of the node at port 9001 (192.168.1.102:9001), - click Connect, and make sure your node appears in the list of environments.

You now have a centralized dashboard to monitor and control all your services !

WordPress

Connect to PHPMyAdmin at https://phpmyadmin.n2.mydomain.com/ using the user root and the password in the secret file :

# cat .secrets/mariadb-rootGo to User Accounts, then click Add user account, and create a new account with the following information :

- User name :

wordpress - Password : the one you will find in the secret file :

# cat .secrets/mariadb-wordpress - Check the option Create database with same name and grant all privileges.

Then head to https://www.mydomain.com/ and finish the installation of WordPress.

6. Backups

No system is complete without a good, battle-tested backup solution, and this post wouldn’t be complete without at least mentioning this aspect of the setup. A lot of solutions are worth considering, and it is up to you to find the most relevant to your case. As a simple example here, we’ll assume that we want to backup to an external server using rsync1. This server might be another VPS or a NAS for instance.

We’ll implement this by defining a simple script that will run everyday in the middle of the night to :

- stop the containers,

- pull the latest updates of the Docker images,

- backup

/srvand/etc, - start the containers again.

It’s simple but definitely crude. The services will be unavailable for some time while the transfer run, which might not be acceptable depending, but it’s good enough for the scope of this post.

First, we need to install rsync :

# apt install rsyncrsync must also be installed on the remote server. On Synology NAS’s, it is installed by default, but the user must have been given access to it in its Applications permissions tab.

Then we need to make sure that we have access to the backup server from the node :

# ssh-keygen -t rsa

# ssh-copy-id -p ssh_port backup_user@backup_server

<enter the password of backup_user>

# ssh -p ssh_port backup_user@backup_serverIf ssh opens up successfully, the connection is setup properly.

If you want to backup to a Synology NAS, take a look at my previous post : Using SSH key authentification on a Synology NAS for remote rsync backups.

Here is a simple script template that does what we want, that we’ll place in /srv/backups.sh :

#!/bin/bash

## Config

SRV=n1

HOST=<backup_server_ip>

PORT=<backup_server_port>

USER=backup_$SRV

BAK_DIR=/volume1/backup_$SRV

TMP=/tmp

PRIO=user.info

TAG=backup

logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i "Starting backups to $USER@$HOST:$PORT$BAK_DIR"

cd /srv

## Containers update

logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i "Updating Docker containers..."

docker compose pull | logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i

## Stop containers

logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i "Stopping Docker containers..."

docker compose down | logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i

## Backup /etc

logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i "Backing up /etc..."

rsync -azXv -e "ssh -p $PORT" --delete-after --backup --backup-dir="$BAK_DIR/etc/rsync_bak_`date '+%F_%H-%M'`" /etc/ $USER@$HOST:$BAK_DIR/etc/etc/ | logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i

## Backup /srv

logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i "Backing up /srv..."

rsync -azXv -e "ssh -p $PORT" --delete-after --backup --backup-dir="$BAK_DIR/srv/rsync_bak_`date '+%F_%H-%M'`" /srv/ $USER@$HOST:$BAK_DIR/srv/srv/ | logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i

## Restart containers

logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i "Restarting Docker containers..."

docker compose up -d --build --remove-orphans | logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i

## Cleap up old images

logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i "Cleaning up old Docker images..."

docker image prune -f | logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i

## Done

echo `date '+%F_%H:%M:%S'` > $TMP/last_backup

rsync -azX -e "ssh -p $PORT" $TMP/last_backup $USER@$HOST:$BAK_DIR/ | logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i

rm $TMP/last_backup

logger -p $PRIO -t $TAG -i "Finished backups"Remember to customize the backup’s destination and to make the script executable :

# chmod +x /srv/backups.shYou may want to check that the scripts works correctly by executing it right now :

# /srv/backups.shThen, we’ll define a simple systemd timer to run this script everyday at 3am :

# vim /etc/systemd/system/backups.service

[Unit]

Description=Daily backups script

[Service]

Type=oneshot

ExecStart=/srv/backups.sh# vim /etc/systemd/system/backups.timer

[Unit]

Description=Runs the daily backups script

[Timer]

OnCalendar=*-*-* 03:00:00

Persistent=true

[Install]

WantedBy=timers.targetReload the config and enable this timer unit :

# systemctl daemon-reload

# systemctl enable --now backups.timerYou can check that it is correctly enabled with the following commands :

# systemctl list-timers

# journalctl -u backups.service1 rsync is a command-line tool that is able to synchronize two directories, whether they are local or remote, by transferring only the files that have changed.

Conclusion

If everything is setup correctly, you should now have :

- a Traefik dashboard on

https://traefik.n1.mydomain.com/dashboard/, - a Portainer dashboard on

https://portainer.mydomain.com/, - the logs of every node and every service in

/logson N1, that you can monitor from your local machine using$ lnav "root@n1.mydomain.com:/logs/*/*"

If you do, congratulations, your servers are working properly !